In DFS tournaments, “stacking” is a common strategy. The concept is straightforward — you want to pair pass catchers with their quarterback because of the correlation between their weekly fantasy scoring. If a QB throws three touchdowns, there’s a good chance at least one of his WRs had a great game.

In best ball, especially in tournaments with large payouts to top finishers, we are looking for spike weeks and high-potential combinations during the playoffs. Stacking also simply works well with the “best ball” format because if your stack hits on a given week, you get a big QB and WR score. If it doesn’t hit, you’ve got a bench to hopefully cover your QB and WR scores for that week, or possibly even a second different stack that has a chance to hit.

However, stacking is less commonly used and discussed in traditional season-long formats. We set out to investigate whether this strategy also makes sense in these leagues. And if it does, how should you adjust your drafting to incorporate it?

Editor’s Note: Our Draft Kit includes all these rankings, dozens of analysis articles, live streams of drafts, team-by-team previews and lots more. It’s just $35 and comes with a $25 FFPC coupon. Click here for more details.

Editors Note 2: Make sure to subscribe to the ETR Podcast for additional context behind rankings and much more

OUR TAKEAWAYS:

This article involves a fairly thorough analysis, and we understand not everyone wants to see all the background work. If you’d like actionable takeaways only, we’ve summarized them in this section.

With the caveat that past returns don’t guarantee future returns (the fantasy landscape is ever changing), it looks like there is an edge to be had by stacking in all season-long formats. Fantasy analysts harp that upside wins championships, but it can be difficult to identify exactly what that means in the middle of a draft. Oftentimes it’s priced into ADP of specific players or something that only seems obvious in hindsight. Stacking is a structural way to build upside into each of your teams, and upside is typically rewarded by the disproportionately large payouts to fantasy league winners.

- If your league has a significant payout for first place (at least 25% of prizepool), always lean towards stacking a QB with a WR/TE when possible

- “Double stacking” (QB with two pass catchers) is likely a good strategy, especially in “top heavy payout” formats like large season-long tournaments. Note that when a QB significantly outperforms his ADP, there are almost always multiple pass catchers on his team that do the same.

- Consider being willing to reach at least 1-1.5 rounds for a QB if you’ve selected a pass catcher of his in the first 8 rounds — especially in tournaments where outlier outcomes are more heavily rewarded

- We prefer drafting the mid-tier of quarterbacks, but if you do decide to draft a QB early, it should almost certainly involve a high upside stack.

- Medium and Big hits matter the most — a player outperforming his ADP minimally does not typically make stacking partners good picks. While it’s debatable whether upside is knowable entering a season, a stack makes more sense when the range of potential outcomes for the pair is wider — think younger or unproven players, new coaches, perceived injury risk, significant changes to teammates, or other variables the market can’t reasonably be certain about

Overview

What we are trying to examine at is “given we have drafted a Quarterback that has a certain quality of season (average, good, great, etc.) adjusted for ADP, how do his WRs and TEs typically perform?” Similarly, if we draft a pass catcher that has a certain quality of season, how does that affect his quarterback?

Before we delve into the analysis, here are some notes for how the analysis was performed:

- ADP references are from FFPC the past three seasons and come from FantasyMojo

- We used 20-round FBG / Classic ADP close to the start of the season

- Only the Top-300 ranked players by ADP for each season were used

- The term “pass catcher” refers to a WR or TE

Quarterback Hit Rates

We broke QBs down into different “hit rate” categories, using all QBs (sample size: 88) with a Top-300 ADP from the past three seasons. Here’s how we defined a QB “hit”:

- To qualify as a hit, a QB has to score above the median result of all QBs in the sample – 293 fantasy points

- Minimum Hit = outperformed ADP expectation by any amount

- Small Hit = outperformed ADP expectation by at least 30 points

- Medium Hit = outperformed ADP expectation by at least 50 points

- Big Hit = outperformed ADP expectation by at least 100 points

Here’s the breakdown of how frequently quarterbacks qualified for each category:

- Minimum Hit: 49% (43 / 88, average of ~ 14 a year)

- Small Hit: 38% (33 / 88, average of ~ 11 a year)

- Medium Hit: 23% (20 / 88, average of ~ 7 a year)

- Big Hit: 13% (11 / 88, average of ~ 4 a year)

Pass Catcher Impact

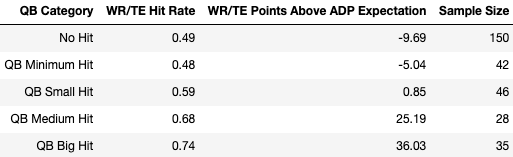

Using QB hit rates, we analyzed how pass catchers (WR or TE ) performed based on how their QB performed. We whittled this sample size down to the 329 pass catchers that had a Top-18 Round ADP rank (216 overall or better). Here were the results for these pass catchers:

All QBs

- 329 sample size

- 54% hit rate (whether or not they outperformed ADP expectation)

- Scored +0.56 points above ADP expectation on average

QB Minimum Hit or better

- 151 sample size

- 61% hit rate

- +/- ADP average of +11.9 points

QB Small Hit or better

- 109 sample size

- 66% hit rate

- +/- ADP average of +18.4 points

QB Medium Hit or better

- 63 sample size

- 71% hit rate

- +/- ADP average of +31.2 points

QB Big Hit

- 35 sample size

- 74% hit rate

- +/- ADP average of +36.0 points

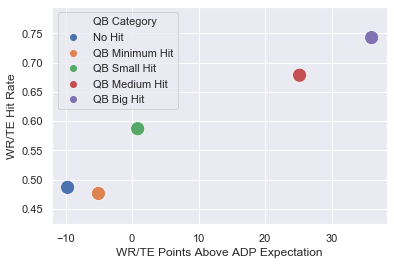

Here’s how it looks if you keep pass catchers confined only in their own groups (ie not as “or better”):

Once we move past a QB Minimum Hit and into a QB Small Hit, we see a big spike in pass catcher hit rate. When we look at a QB Medium or Big Hit (almost 7 QBs a year fit this bill, not an unreasonable threshold), the hit rate continues to climb, but more importantly the average points above expectation spike.

Here are the 11 QBs the past 3 years that qualified as ‘Big Hits’ and their respective pass catchers with a 216 ADP rank or better:

- Alex Smith KC 2017 (342.6 FFPC Points, ADP of 217, QB25)

- Tyreek Hill +51 Points (relative to expectation), 15 games

- Travis Kelce +63 Points, 15 games

- Blake Bortles JAX 2017 (299.6 FFPC Points, ADP of 259, QB28)

- Allen Robinson -176 Points, 1 game

- Allen Hurns +1 Points, 10 games

- Marqise Lee +53 Points, 14 games

- Ben Roethlisberger PIT 2018 (405.2 FFPC Points, ADP of 126, QB8)

- JuJu Smith-Schuster +100 points, 16 games

- James Washington -50 points, 14 games

- Antonio Brown +67 points, 15 games

- Vance McDonald +61 points, 15 games

- Dak Prescott DAL 2018 (340.7 FFPC Points, ADP of 200, QB21)

- Amari Cooper +13, 15 games

- Allen Hurns -54, 16 games

- Michael Gallup -14, 16 games

- Jared Goff LAR 2018 (373.2 FFPC Points, ADP of 159, QB16)

- Cooper Kupp -15, 8 games

- Robert Woods +131, 16 games

- Brandin Cooks +62, 16 games

- Patrick Mahomes KC 2018 (482.1 FFPC Points, ADP of 144, QB14)

- Tyreek Hill +110 Points, 16 games

- Travis Kelce +156 Points, 16 games

- Sammy Watkins -43 Points, 10 games

- Matt Ryan ATL 2018 (417.2 FFPC Points, ADP of 151, QB15)

- Austin Hooper +90 Points, 16 games

- Calvin Ridley +98 Points, 16 games

- Mohamed Sanu +84 Points, 16 games

- Julio Jones +92 Points, 16 games

- Mitch Trubisky CHI 2018 (305.3 FFPC Points, ADP of 244, QB27)

- Anthony Miller, +7 Points, 15 games

- Allen Robinson -20 Points, 13 games

- Trey Burton +5 Points, 16 games

- Lamar Jackson BAL 2019 (457 FFPC Points, ADP of 120, QB9)

- Marquise Brown +53 Points, 14 games

- Miles Boykin -42 Points, 16 games

- Mark Andrews +113 Points, 15 games

- Dak Prescott DAL 2019 (399.8 FFPC Points, ADP of 151, QB15)

- Jason Witten +77 Points, 16 games

- Amari Cooper +40 Points, 16 games

- Michael Gallup +83 Points, 14 games

- Blake Jarwin +8 Point, 16 games

- Jameis Winston TB 2019 (388.5 FFPC Points, ADP of 136, QB13)

- Mike Evans +13, 13 games

- OJ Howard -77, 14 games

- Chris Godwin +74, 14 games

Nearly 75% of these pass catchers exceeded their ADP expectation, and they did so by an average of 36 points, a pretty massive figure. While you can’t discount the chances of injuries, it is worth noting that a lot of the pass catchers who failed to meet expectations in this scenario did not play a full season.

It’s also noteworthy how many pass catchers on the same team are propped up by a big QB season. 2018 Jared Goff had Robert Woods and Brandin Cooks exceed ADP expectations by nearly 200 points combined, while Cooper Kupp just missed his ADP expectation despite playing only 8 games. 2018 Matt Ryan had four pass catchers roughly exceed their ADP expectation by 90 points each.

There are even more examples, but you can discern them from the listing above. The point is you don’t want to stop at single stacks. Even in non best ball season-long formats, double stacks have a desirable and attainable upside.

Let me repeat – they have an attainable upside. 11 QBs the past three years (nearly 4 a year) were big hits. Their cost ranged from QB8 to QB28, with none of them being selected prior to pick 120 (last pick of the 10th round). Most were selected in Rounds 11-13.

Reversing the Correlation

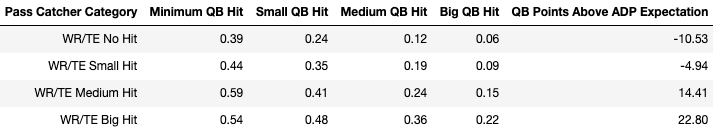

We flipped the analysis and started with the pass catcher; the results are similar.

We broke down pass catchers into the following categories:

- No Hit = WR/TE underperformed ADP expectation

- Small Hit = WR/TE overperformed ADP expectation by <= 30 points

- Medium Hit = WR/TE overperformed ADP expectation by 30 – 74 points (67th – 85th percentiles)

- Big Hit = WR/TE overperformed ADP expectation by 74+ points (85th – 100th percentiles)

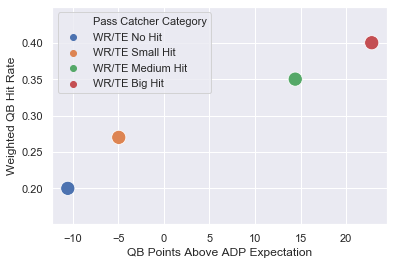

Here’s how often a QB had a certain hit rate (minimum, small, medium, or big) and by how much they over or underperformed ADP expectation on average based on nothing more than the Pass Catcher Category.

Once again, the focus immediately is drawn to medium or big hits. When a pass catcher was in either one of those categories (and 33% of them were), their respective QB saw big increases in hit rate and points relative to ADP expectation. For example, QBs who had a pass catcher who did not hit had a QB Medium Hit rate of just 12%. That number tripled to 36% for QBs who had a pass catcher that was a big hit.

If you break it down to simple hit / no hit, it looks like this:

QBs with pass catchers considered a hit of any type were 34% more likely to be a “QB Hit” than non-hits, and their points relative to expectation rose by 19.6 points.

How is this actionable?

It’s obvious that if your pass catcher hits, your QB is much more likely to hit, and vice versa. But, how does this affect your draft? More directly, how many picks/rounds earlier should you take your QB or pass catcher than you normally would? How many projected points should you sacrifice to make a stack instead of taking a player you have with a higher projection at that position?

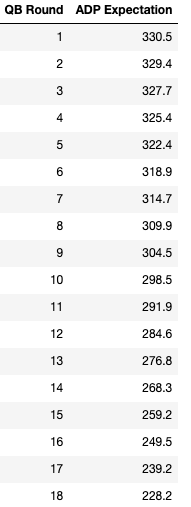

Let’s look at ADP expectation by Round with a super simple model:

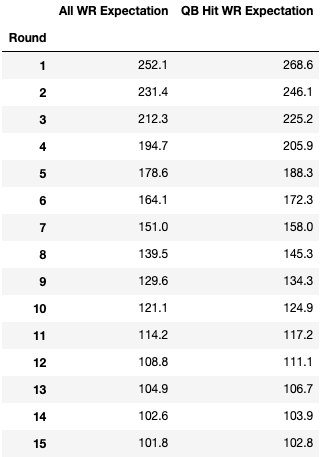

More or less, your mean WR expectation jumps up nearly a full round if you assume the QB hits versus if you’re unsure if the QB hits or not (i.e. everyone). For example, a Round 3 WR with a QB hit is expected to score 225 points. Compared to all WRs, that’s closer to their Round 2 Expectation (231 points) than the same Round 3 expectation (212 Points). We see roughly the same dynamic throughout.

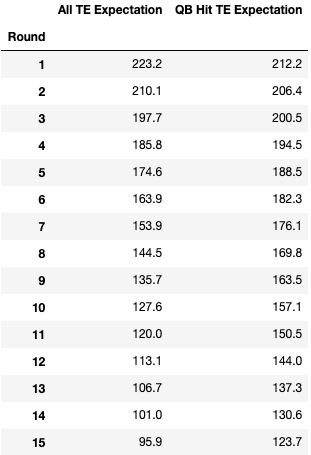

The story is similar for TEs. The Round 1-2 expectation is a little lower, which is mostly due to small sample size issues for the TE position. What’s most important is that throughout the chart, you can see that TEs whose QB hits have a big advantage over the full TE group. This is even more pronounced than the WR chart (a half round to full round advantage) once we get to the fifth round and beyond (a full 1 – 3 round advantage for TEs).

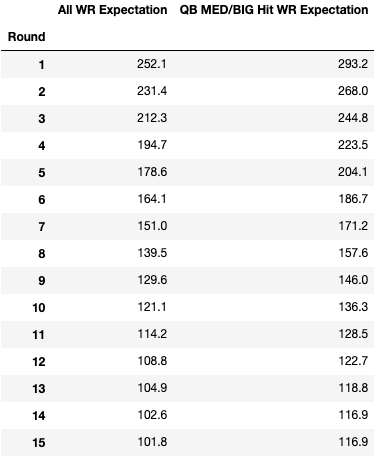

Keep in mind, this is just splitting pass catchers between QBs that hit and QBs that don’t hit. It’s more pronounced if we look at QBs who achieved a Medium or Big hit (outperforming ADP by 50 or more points, 23% of all Top-300 ADP QBs hit this threshold each year):

This makes it seem like you should be willing to take your stacked WR a full round to a round and a half earlier, perhaps even two rounds earlier when we move into the double-digit rounds.

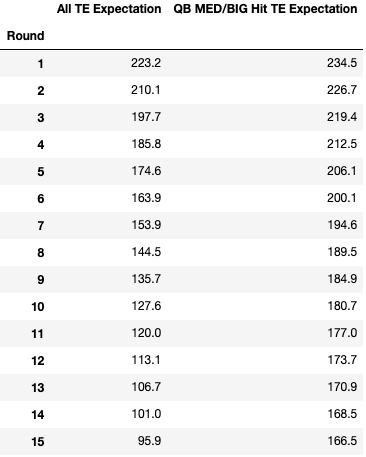

Wow, when we look at the ADP expectation of TEs with a Medium or Big QB Hit, it’s a massive difference. The small sample size is likely skewing the magnitude larger (15 players), but it’s pretty clear that you want to stack your TE with the QB, especially as you get later in the draft.

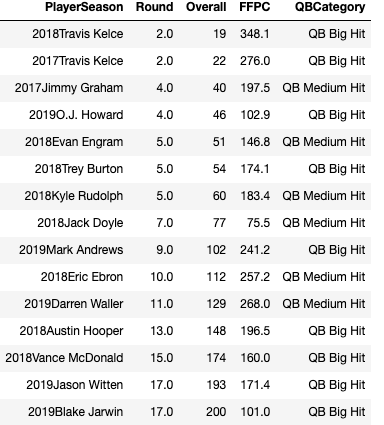

Here are all 15 TEs in that sample:

How should I plan for my stack?

While the above information shows that you should be willing to take a pass catcher at least a round early to stack with your QB, it can still be tough to know exactly how to implement a stacking strategy when you’re waiting until Rounds 8 – 13 to take your QB(s).

In a perfect world, you’ll want to make sure you select at least 3 pass catchers in rounds 1-8 where you would be comfortable taking their QB in the middle rounds at ADP. You likely won’t need to reach on anyone, simply just take whichever QB falls to you later in the draft, as you’ve already preselected pass catchers with QBs you like. Another option is to select pass catchers a little bit early (maybe half a round to a full round) who are attached to QBs you are higher on than the market, knowing you have a realistic chance of drafting them later on by reaching. By not reaching over a full round, you mitigate some of the risk associated with possibly getting sniped on the QB of your choice, but you leave room for upside to complete the stack at a reasonable cost.

It is worth considering the math on working from the pass catcher out. As we showed earlier, QBs who have pass catcher hits were 34% more likely to be a “QB Hit” than non-hits, and their points relative to expectation rose by 19.6 points.

Since we’re generally taking QBs in Rounds 8 – 13 (ideally 10 – 13) or so, let’s look at the shift in QB expectation specifically based on pass catcher hits in the first 8 rounds of a draft.

If you look at all pass catchers who had a Top-8 round ADP the past three seasons and a QB with a Top-300 ADP in the same season, you get a sample size of 150 pass catchers .

On average, the QBs attached to these pass catchers had a hit rate of 55% and underperformed ADP by 3.4 points.

51/150 (34%) of these early pass catchers were a medium hit or better, meaning they outperformed their ADP by at least 30 points.

On average, the QBs attached to these pass catchers had a hit rate of 65% (10-point increase) and outperformed ADP expectation by 13.3 points (a 16.7 point increase).

A 16.7 point increase in ADP expectation is a big deal at a position where ADP expectation is relatively flat, especially in the QB rounds we’re zoning in on (10 – 13).

Essentially, this means you should be willing to take your QB at least one round earlier than usual if you have drafted one of their pass catchers in the first 8 rounds. If you are drafting off projections, you should add nearly 15 points to QBs whose pass catchers you drafted in the first 8 rounds. The takeaway here is that while it’s ideal to not have to reach for anyone, it’s perfectly acceptable to do so if you think there’s a good chance you’ll miss out on a stacked QB in the middle rounds.

CLOSING THOUGHTS:

There are multiple ways to get an edge in fantasy football. In less competitive leagues where opponents are making huge errors valuing players, any edge to be gained from stacking will pale in comparison to using better rankings, being mindful of ADP or opponent tendencies so you can draft players as late as you possibly can, etc. But as leagues get more competitive, the value of stacking should not be discounted, simply because very few of our opponents are currently doing it.

In addition to our takeaways near the top of the article, we think that in a typical season long league, at a minimum, stacking should be a tiebreaker between a few players. And moving up less than a round on a player to complete a stack is likely a good idea. In formats with bigger payouts to first, like tournaments, we think stacking is nearly mandatory if you’re trying to maximize your chances of winning, and your teams should contain multiple pairs of QBs with pass catchers, if possible.