IMPORTANT Editor’s Note: Limited time offer through Tuesday — Make a deposit on Underdog Fantasy and get $25 on top for free! Just use this link and promo code ETR after your deposit. This offer is good for both new AND existing Underdog players.

Earlier this offseason, I evaluated the impact of stacking on the regular season of the Underdog Best Ball mania tournament last season. In this article, I am going to look at the impact of roster construction. More specifically:

- What positions should you draft early?

- How many of each position should you draft?

- How do you draft dynamically?

Before digging into this data, it is important to digest it with a critical eye. Players who had outlier seasons (Travis Kelce at TE for example) will have an outsized impact on one year of roster construction data. Similarly, ADPs will change from one year to the next. So while I expect to glean some interesting findings, it’s not a good idea to assume the exact same thing is going to happen next year. We must try to apply the lessons from previous seasons to the specific landscape of the upcoming season, thinking through how changing positional scarcity, ADP, and specific values could impact the correct roster construction approach.

Overall Roster Construction

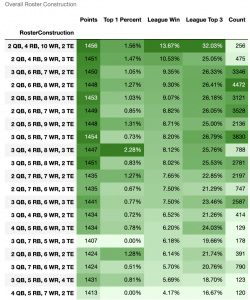

Let’s dive right into how specific roster constructions fared, filtering out constructions that weren’t used at least 100 times:

*League Win and Top 3 rates are estimated based on regular season scores. For example, all teams with a Top 8.3% score were assumed to have won their league. All charts are sorted by win rate.

There are a few things I want to point out right off the bat. First of all, when we chop things up like this, we see how randomness and volatility can wreak havoc to an extent (especially if you focus too much on the Top 1% outcomes). For example, the construction with by far the highest win rate is 2 QB, 4 RB, 10 WR, 2 TE. However, a very similar 3 QB, 4 RB, 9 WR, 2 TE construction fared poorly. Now, we will see that 2 QBs is optimal, which assuredly explains some of the difference. However, it’s unlikely that switching 1 WR to 1 QB in this construction takes it from the best possible construction to one with a negative expected value. The former strategy is likely better than the latter strategy, but I suspect randomness propped up the 2 QB-10 WR version of this construction to an extent, similarly dragging down the 3 QB-9 WR version.

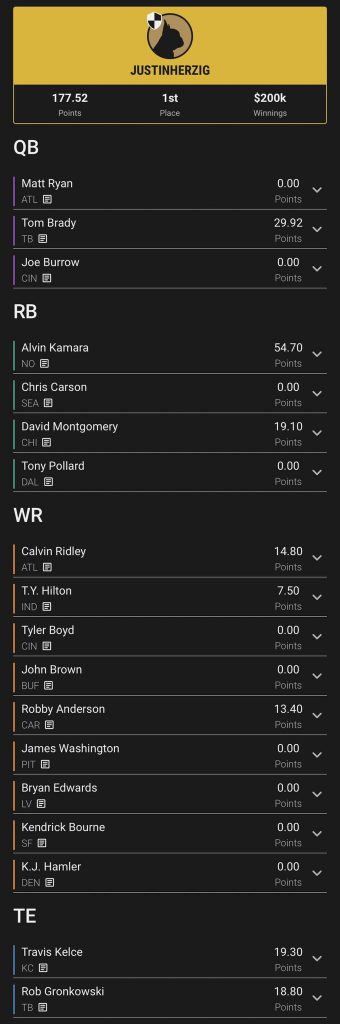

As anecdotal evidence, I’d be remiss if I didn’t point out that our own Justin Herzig won the entire Best Ball Mania tournament ($200k grand prize) with a 3-4-9-2 construction:

In general, Justin’s team is a great example of how structure in best ball can generate upside, perhaps even more so than the types of player you choose. Justin outlined How to Beat Best Ball earlier this offseason.

With that said, it’s great to see the top two constructions by League Win rates are examples of the Hyper Fragile roster constructions I hit on as a viable strategy last offseason. We’ll dive much deeper into that strategy and how and why both it and Zero RB were successful despite being at odds with one another on the surface. One of the keys to the success of the Hyper Fragile strategy is the ability to find solid starting WRs and upside bets throughout the draft combined with the weekly variance of the position. It’s the easiest positions to make up for quality with quantity.

Meanwhile, it’s much more difficult to substitute quality for quantity at the onesie positions. There were seven specific constructions that yielded a League Win rate higher than that of randomness (8.3%). Six of the seven were 2-QB teams. On the other end of the spectrum, there was a clear drop off in Win Rate for the bottom seven teams. Only one of those seven teams rostered 2 QBs. The results at TE were a bit more mixed, and we’ll get to why that is when we dig into TEs specifically later in the article.

While most of the successful teams went with just two players at at least one of the onesie positions (either QB or TE), the 3 QB, 4 RB, 8 WR, 3 TE and 3 QB, 5 RB, 7 WR, 3 TE teams performed okay. In particular, the 3-4-8-3 allocation showed a ton of upside (by far best Top 1% rate of any construction). This is a good example of how you can think critically and get away from “optimal” strategies, such as only drafting two QBs, if you’re cognizant of how you’re spending your capital overall. These teams likely spent early picks on the RB-WR positions (particularly RB) to gain an edge in quality there and then survived the onesie positions by taking three of each. I don’t think it’s an ideal build, but all drafts fall differently. It’s possible there wasn’t an opportunity to get a high-end onesie position earlier in some of these drafts, making this construction a smart adaptation on the fly. It’s something to keep in the back of your mind as we enter a season where QB ADPs are likely to rise, which might make it more difficult to grab two top-half QBs at a reasonable cost and be done with the position.

The other takeaway from this initial chart is that drafting a lot of RBs in a vacuum is bad. The best win rate for a seven-RB team is 7.7%, but we’ll see shortly that there are some exceptions to this based on how you start your draft.

Position by Position Breakdown

Quarterback

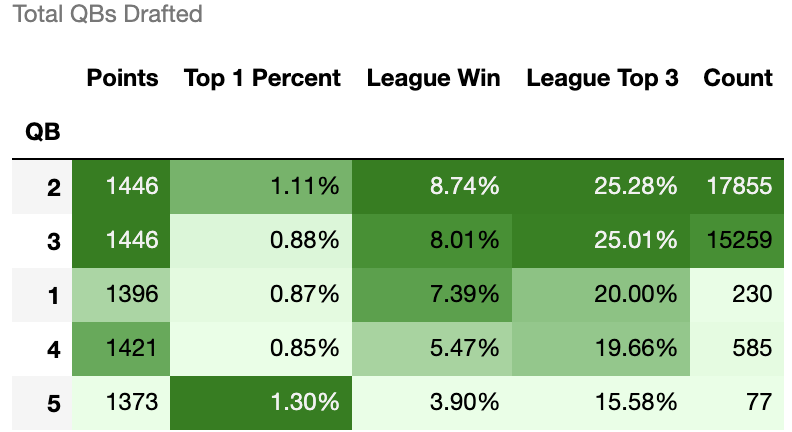

Let’s start by simply looking at the success rates based on number of QBs rostered:

Takeaways:

- Drafting two QBs is clearly the optimal strategy in a vacuum.

- The high Top 1% rate for five QBs drafted is a great example of how viewing things through that prism can be skewed. It’s clearly a horrible strategy, but it “pops” because a single team out of 77 people who foolishly drafted five QBs happened to run into a Top 1 Percent score. I like having that column to try and envision very high-end upside, but we must be aware of the havoc small samples can wreak.

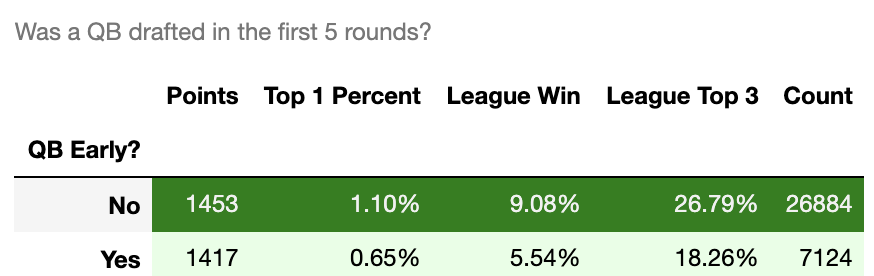

Digging deeper, it becomes clear that taking a QB early in 2020 absolutely killed win rates, but less clear how much of that was a structural problem.

Now, this chart isn’t entirely fair because there were essentially only three QBs drafted consistently in the first five rounds: Patrick Mahomes (2,834), Lamar Jackson (2,834), and Dak Prescott (1,054). This trio represented 92% of all early QBs drafted. Lamar Jackson had a disappointing season, and Dak Prescott got injured early in the season. Mahomes teams had slightly elevated win rates across the board.

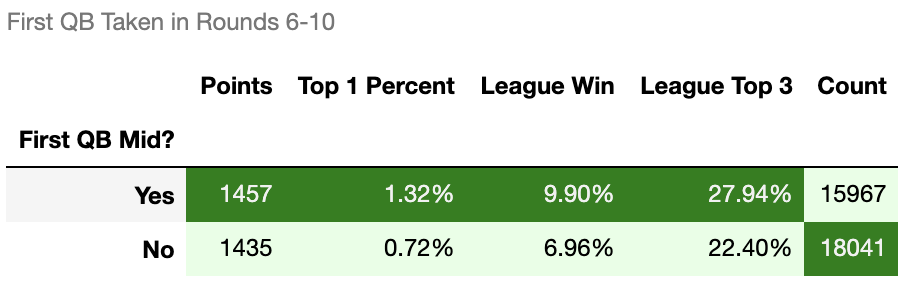

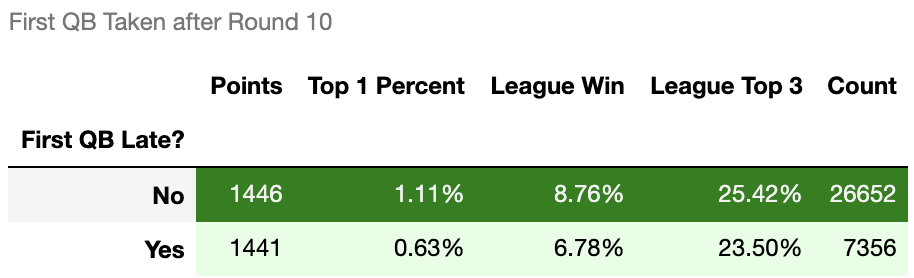

Let’s see how teams fared drafting their first QB in the mid-tier (Rounds 6-10) or drafting their first QB late (after Round 10):

Again, there is some bias here as the Rounds 6-10 QB group benefited from hits on Josh Allen, Kyler Murray, Deshaun Watson, and others, but that’s sort of the point. We saw a separation in weekly QB ceiling this past season that was more pronounced than in other years, as a combination of pass-heavier offenses and QBs with dual-threat upside become more prominent. This trend is likely here to stay, which makes it appealing to focus on getting your first QB in this range again. You get similar benefits of drafting an Early QB (high weekly ceiling, ability to only draft two QBs total) without the high opportunity cost of passing on a skill player in the first five rounds.

This might seem obvious in retrospect and ADP dynamics could change things, but drafting only two QBs with your first coming in the Rounds 6-10 range was a meaningful edge last season. More teams than not either drafted their first QB early or late. We need to be more focused on individual ceiling at QB than in past seasons.

Running Back

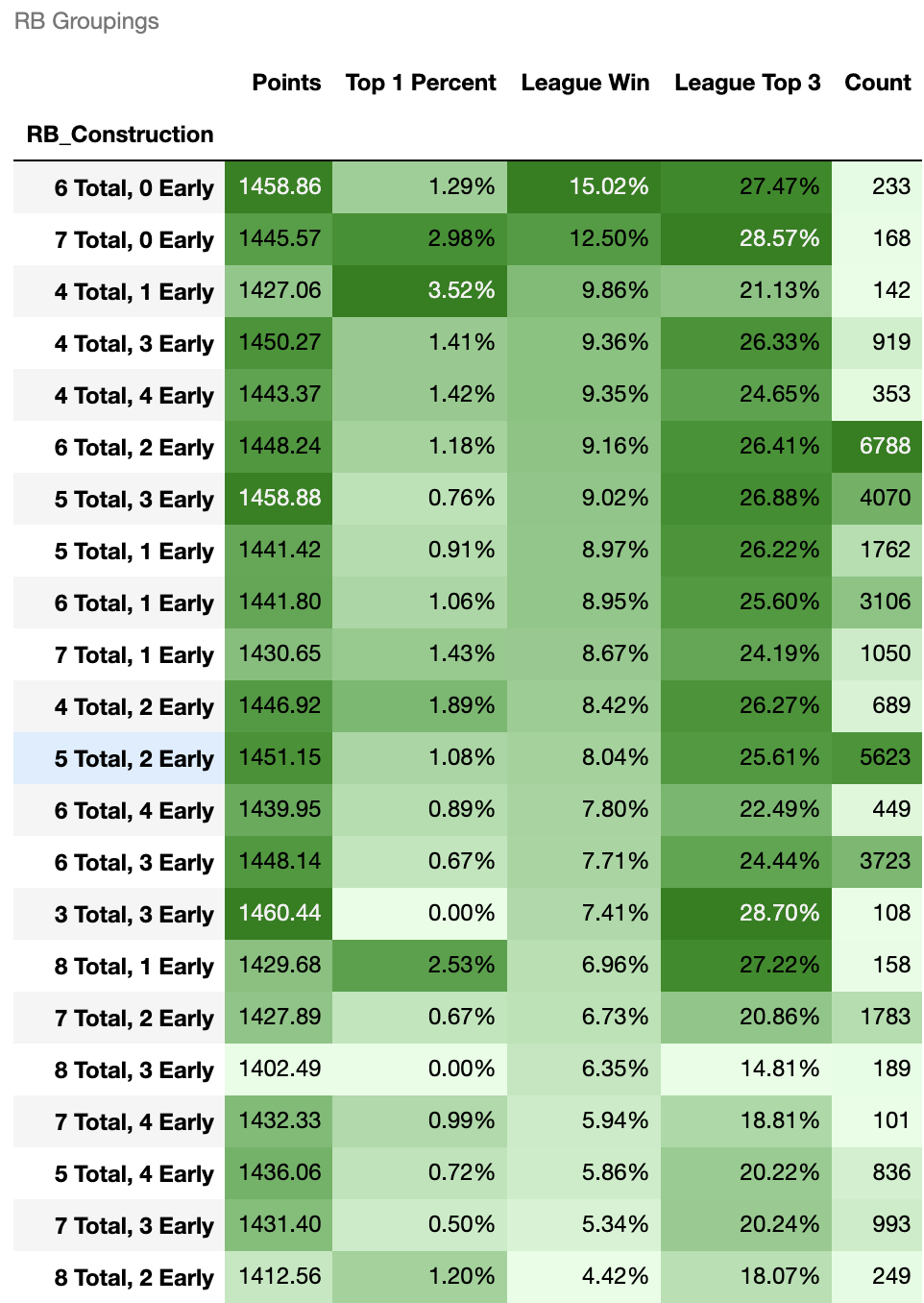

At the RB position, we’ll dive straight into specific RB groupings, combining the total number of RBs drafted with how many of those RBs were drafted early (first five rounds):

Most of the observations in this article need to be taken in context. Strategies that seem optimal may not be in specific scenarios, and you need to be flexible and use critical thought. However, if you take one thing away from this article to blanket apply to all of your rosters, let it be this:

Do not draft RBs Early *AND* draft a lot of RBs

There is no circumstance in which this strategy makes sense, no context or draft day dominoes that should lead you here.

My friends like to joke that I have a “never middle” philosophy. What they mean by this is I like to try extreme strategies in whatever game we are playing. For example, in dynasty leagues I am often either full on rebuilding or going all in to try and win a championship. Luckily for me, the data suggests that the “never middle” philosophy performed well at the RB position. The strategies that showed the most upside were either Hyper Fragile or Zero RB (draft zero or one RB early, get many late).

The two strategies that had the highest league win rates, by a large margin, were full Zero RB strategies – teams that drafted zero RBs early but collected a large amount of RBs in total (6-7). These teams also had surprisingly high Top 3 finish rates, albeit in a small sample size. I do think there’s some bias in the data in the sense that only sharper players seem to utilize a Zero RB approach, and these players would likely have above average win rates regardless of the strategy they chose. Still, the results are extreme and hard to ignore. Teams that went with the “Anchor RB” approach (basically Zero RB but with one anchor RB drafted early) also had League Win and Top 1 Percent rates above average. Despite their success, it is surprising that the full Zero RB teams did so much better. My guess is that is a result of a combination of sample size (the Anchor RB strategy was much more prevalent) and some season-specific breaks (injuries to Barkley and CMC, who were popular anchor RBs in that strategy).

Meanwhile, every single iteration of the 4-RB Hyper Fragile strategy had above average League Win rates and stellar Top 1 Percent rates. In a small sample, the most extreme version of Hyper Fragile, 3 RBs Total and all of them early, posted below average rates but actually registered the highest average score. The Hyper Fragile strategies collectively were pretty neutral in terms of League Top 3 rates, which is an excellent sign. For a strategy that often gets dubbed as a “tournament only” strategy, it’s actually useful in all formats because you’re increasing high-end upside without sacrificing your floor. As personally a big proponent of this strategy, this upcoming season I will try more versions of it where I draft one or two RBs early instead of three or four.

At this point, it might seem confusing that two generally opposed strategies both did well. One approach is to draft RBs early and not draft a lot of them while the other is to draft at most one RB early and take a lot of them. What gives? Well, as I outlined in my Hyper Fragile article last season, these two strategies are actually rooted in the same principles. RB is a high variance season-long position because its success is dependent less on skill than other positions and more on health and opportunity. In the Zero RB approach, which is more viable in Underdog’s best ball format than I expected and stated in my Hyper Fragile article last season, you’re capitalizing on this variance by limiting early draft capital and making many small bets later on. In the Hyper Fragile approach, you’re capitalizing on this variance by assuming the less controllable factors (health and opportunity) break favorably for you on your early picks, allowing you to clear up roster spaces to take advantage of the weekly variance of the WR position.

This is a situation where you should adapt to how the draft is falling early since you have two strategies that are viable despite very different starts.

Of course, there are some “middle” strategies that did alright (3 Early RBs, 5 total; 2 Early RBs, 6 total), but that’s about the maximum combined capital investment you should be making at the position. All of the following strategies performed poorly across the board:

- 4 Early, 5 Total

- 3 Early, 6 Total

- 4 Early, 6 Total

- 2+ Early, 7+ Total

Wide Receiver

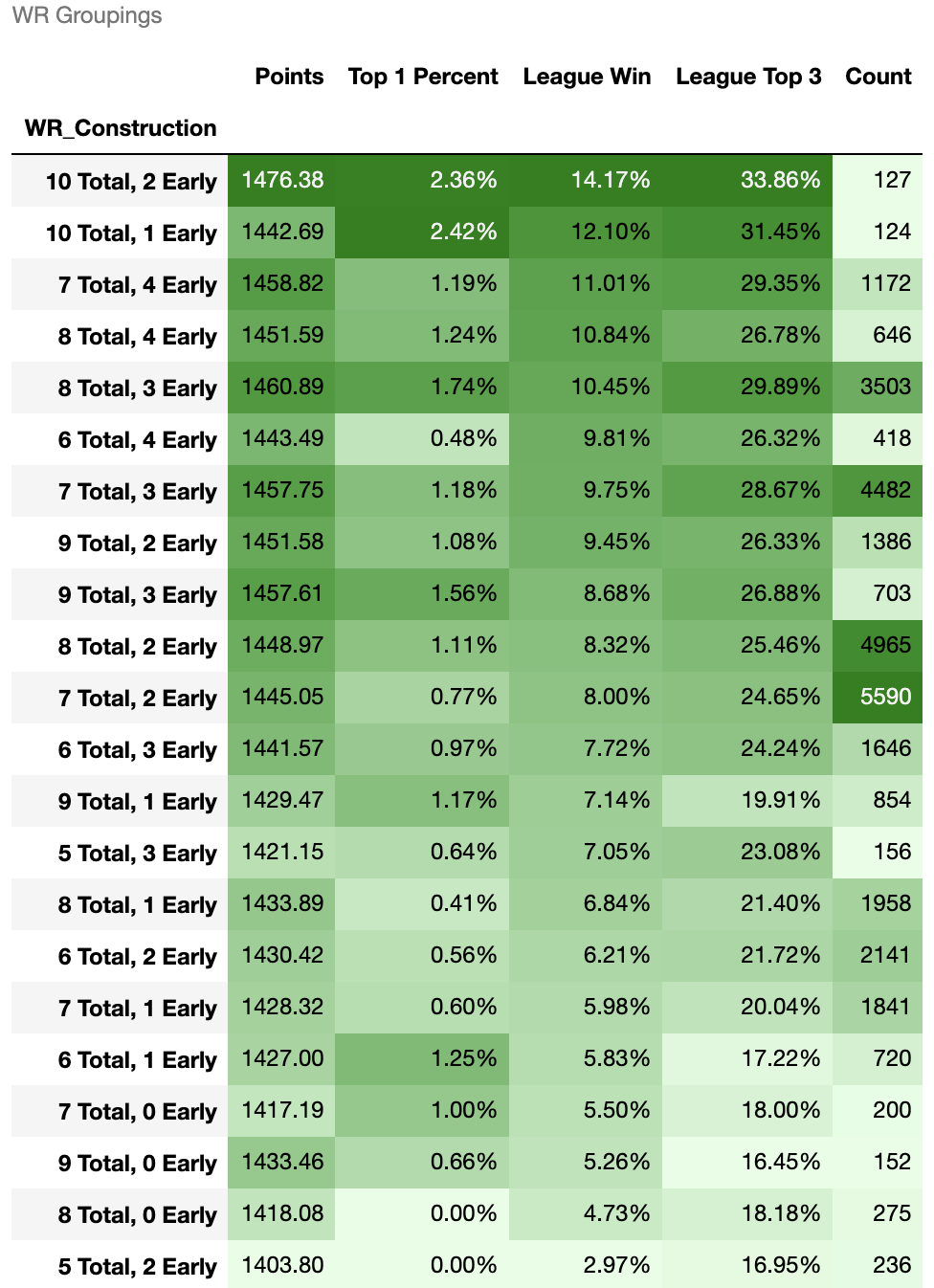

Here are the WR Groupings (same methodology as the RB Groupings chart above):

We don’t have to spend too much time on the WR position because it’s highly correlated to the RB position. When you’re taking a Zero RB approach, you’re naturally drafting more WRs early and less total. Conversely, when you’re taking a Hyper Fragile approach, you’re naturally drafting less WRs early and more total.

One point I do want to stress at the WR position, though, which is very different from managed leagues is that you can make up for quality with quantity at WR. While it’s a small sample size, the teams that drafted 10 WRs performed very well across the board. WR has more weekly variance than the RB position, and you can get ceiling performances from players lower in the draft even if they are seeing limited opportunities. Such performances are impossible to predict on a weekly basis, but lucky for us, we don’t need to predict them in best ball.

WR Takeaways:

- You can make up for quality with quantity by drafting 9-10 WRs in total, allowing you to implement some combination of elite TE, elite QB, and/or Hyper Fragile strategies.

- The other advantage to drafting a high quantity of WRs is it allows you more flexibility to stack multiple pass catchers with your QB without sacrificing value.

- You still want to draft at least one WR early, and if you’re drafting less than 10 WRs total, you probably want two or more early.

- You want at least seven WRs regardless of how many you draft early, but a heavy WR early approach does allow you to stop at seven (ie a Zero RB approach).

Tight End

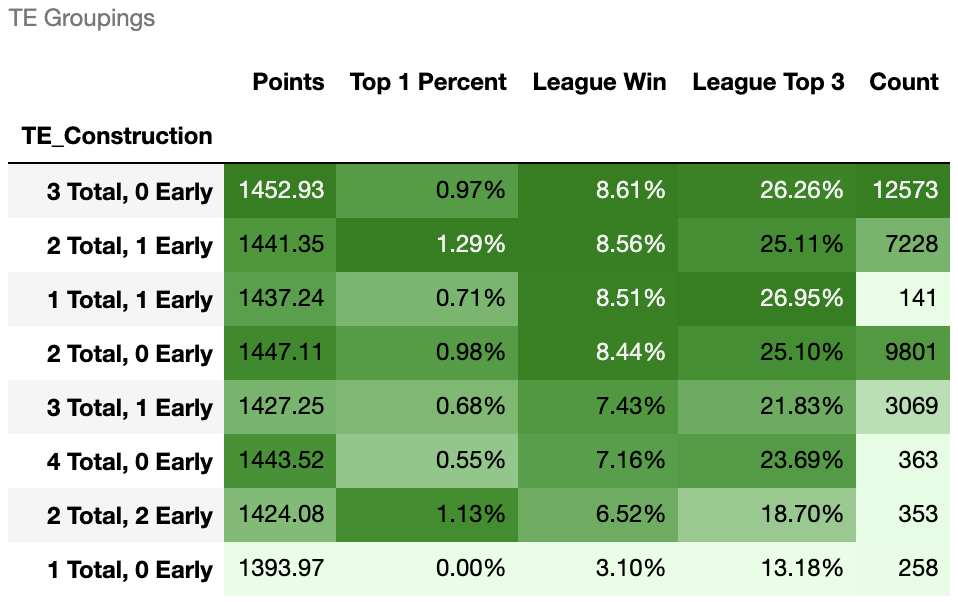

At TE, you’re really trying your best to find a stud or a breakout candidate whose score you can use on an almost weekly basis. As a result, the overall roster construction isn’t that important, but we do have some takeaways:

- If you don’t draft an early TE, you can draft two or three total. Don’t be misled by the order of the chart above; the rates across the board were pretty similar whether you finished with two or three total.

- If you do draft an early TE, you should stop at two total TEs drafted. The third TE becomes superfluous and results in a large decrease in win rates as you’re essentially wasting a roster spot.

- Drafting two TEs showed some upside in Top 1% scores, but performed very poorly in the more stable metrics. My inclination is that the opportunity cost is too high. Again, this circles back to the idea that the best possible outcome at TE is that you find one TE whose score you can use the vast majority of the weeks (something that becomes apparent in my stacking review as well). However, you can still use the TE2 in flex, and it’s possible the win rates here improve given how poorly the high-end TEs outside of Kelce performed last season (Andrews, Ertz, Kittle). As always, it’s important to understand how micro outcomes can affect the macro results in a given year. We don’t want to be too reductive when better performances from Andrews, Ertz, or Kittle last season could have meaningfully improved the results of 2 TE early teams (or if Waller had been drafted earlier). I’m still inclined to avoid this strategy unless I am able to accomplish it at high value relative to ADP.