I spent the beginning of my professional DFS career as a cash-game player, focusing on one optimal lineup. Over the last few years, I’ve switched my focus almost exclusively to large-field tournaments. The transition has been a successful one, resulting in a dozen six-figure scores and consistent year-over-year profit. It’s also required me to shift the way I think about the strategy of DFS on a daily basis. These are the biggest mistakes I see people making in large-field NFL DFS tournaments.

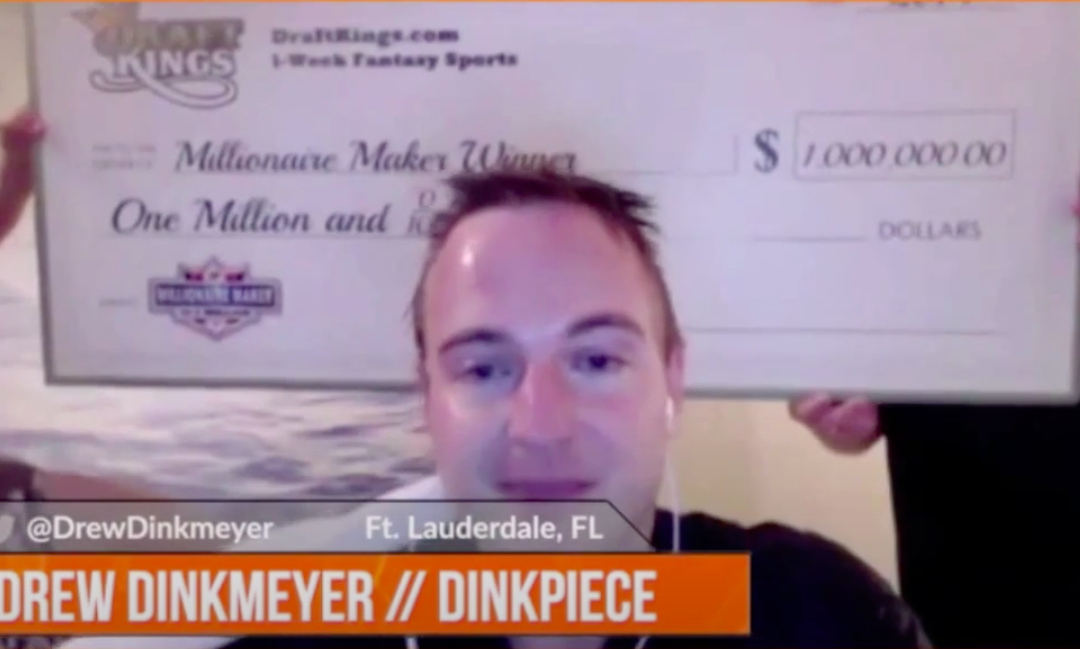

Editor’s Note: Drew Dinkmeyer is officially a member of the ETR team! He’ll be a big part of our NFL product and the Head of NBA. For more information on our products, click here.

1. Not Enough Correlation

Correlation is one of the most important elements of playing large-field tournaments in NFL DFS. In DFS tournaments, our goal is to finish inside the top 1% of all lineups. In order to generate these results, you will need individual outlier performances all coming together in the same lineup. Most DFS players acknowledge this need by stacking their quarterback with pass-catching options, typically wide receivers or tight ends; but they often don’t go far enough.

The mistake is made when DFS players are in pursuit of the perfect lineup. The idea is to find a lineup filled with multiple-touchdown upside and if you can choose all of the individual pieces that hit you will be rewarded handsomely. This is clear and logical thinking that hits on a few of the key principles we want to build on. The problem is it’s extremely difficult to find all of the right pieces individually. Tournaments are already hard enough, aiming for perfection makes them harder.

Think of it this way. If you were looking for needles in a haystack would you rather they be magnetic needles or not? Either way it’s going to be difficult to find a bunch of needles in a haystack but it will be easier if some of them clump together. This is how the top performances work in NFL DFS.

An outlier quarterback performance will often support multiple teammates. A quick long touchdown not only comes with the benefit of scoring fantasy points quickly, but can speed up the pace of play for the entire game. These performances can clump together and you’re improving your odds of finding many of them in the same lineup when you emphasize correlation.

It’s typically not just enough to stack your quarterback with a pass catcher, you’ll typically want more players from the same game environment than just those two. Additionally, the pieces that aren’t primarily from one “game stack” can have correlation upside as well. A lineup game-stacking the Chiefs and Chargers can still have miscellaneous roster spots that correlate well with one another. A simple stack surrounded by individual pieces that don’t correlate is decreasing your odds by aiming for a harder target.

2. Evaluating Upside

DFS players often think of upside solely in the context of a player’s performance profile. In the NFL, players with the ability to break off big plays are sorted into the “upside” or “GPP play” bucket and those who rely on compiling volume are sorted into the “safe” or “cash game” bucket. There is rarely further conversation about relative upside but DFS is a game of relative outcomes. Your winnings are decided not by how many points you score but instead by what place you finish in. The value of players in your roster isn’t determined by raw points scored but by how many points they scored relatively to the salary they cost. Everything is relative. Thus upside should be discussed similarly.

Upside should always be evaluated relative to price tag and ownership. Price, Performance, and Ownership are the three factors that move the needle on your winnings in tournaments. The merit of any individual play in tournaments should be framed within these three characteristics. The same player priced $1,000 cheaper than his current price, holds a higher upside. The performance profile didn’t change, but the change in price makes the upside more valuable than it was before. Similarly, two identical players in performance profile and price tag do not have the same upside if one is going to come with half of the ownership of the other. The lower owned option separates your lineups further from the field with their performance. This is more valuable in a game where winnings are distributed by relative performance.

DFS players often make the mistake of evaluating just one of the three upside characteristics necessary for success.

3. Understanding Ownership

This is one of the most challenging concepts in DFS and thus where some of the biggest mistakes are made. It’s easy to speak in generalities about ownership but it’s harder to execute in practice.

Let’s start with individual plays and then work into overall lineup construction.

A good contrarian play has multiple paths to success relative to the field. They are some combination of underpriced, under-owned, and possess an opportunity advantage over similarly priced options. The opportunity advantage could be projected touches/targets, a path to multiple touchdowns due to scoring environment, or the upside advantage of being correlated with the rest of your lineup. Each player should be weighed against players priced around them. When profiles are similar, the lower owned option is the preferred target.

A bad contrarian play has limited routes to success. They have a low opportunity set relative to similarly priced options and they’re primary value is derived solely based on low projected ownership.

A good chalk play has dominant characteristics compared to their similarly priced competition. They have an overwhelming opportunity advantage.

A bad chalk play is when the opportunity advantage a player has compared to similarly priced options is smaller than the ownership gap between them. A bad chalk play has a number of paths to failure that aren’t being appropriately priced into the ownership. A bad offense or game environment, unclear path to holding the opportunity, or simply playing a highly variant position.

In general, you want to pair good contrarian plays with good chalk plays and you want to emphasize correlation in lineups that feature all of those good plays.

In terms of overall lineup construction, total ownership should be considered. Our own Adam Levitan has analyzed winning Millionaire Maker lineups on DraftKings in the past. This research can give some general thoughts to lineups in large field GPPs. Generally, you would like to keep average ownership by position to under 15 percent (a sum ownership of under 110-125 percent is another way to look at things) and your lineups should feature at least one player that is targeted for below five percent ownership.

The challenge to understanding how to leverage ownership in your decision-making in DFS is that the projected ownership of a play is an important component in the evaluation of the play, but it isn’t the only component. DFS players make mistakes when ownership is the sole focus of their decision point. Instead of identifying any low owned play as a good contrarian play, a more holistic approach to analysis is necessary.

4. Ignoring Late Swap

Using late swap is an easy way to improve your return on investment over time.

Most DFS players identify and use late swap only when a player injury status is downgraded and they want to upgrade their lineups by removing that player. This is the original idea behind the tool and the one utilized most frequently. With very few times a year that require this need, late swap is a tool that collects dust for most.

Savvy DFS players understand that late swap is a tool that can be utilized every single slate. Late swap is simply a tool that allows you to make decisions with more information. When described in this manner, it’s something that everyone should be interested in utilizing. Every DFS player at one point or another feels like they could use more information to make a decision. Late swap is that tool.

When utilizing late swap and making adjustments to existing lineups for late games, DFS players have substantially more information at their disposal. You have the performance of the players in the lineup. You have the performance of players utilized by the field. You have the ownership of players already utilized which paints a clearer picture of remaining ownership. All of these data points can help provide information about where your lineup sits and if it can benefit from some change.

There will be plenty of times the added information results in no change at all, but the times when a change is clearly needed are pure upside opportunities to salvaging return on investment. The clearest opportunities are lineups that are off to a bad start and the remainder of the lineup is filled out with players that project for heavy ownership. If those players perform well, the lineup starts from behind and finishes behind as it ascends with everyone else. However, if you swap out from highly owned to lower owned plays the lineup has a chance of getting back into cashing range if the highly owned players fail.

If you’re passing on these opportunities, you’re sacrificing opportunities to improve your returns.

5. Managing Expectations

NFL DFS GPPs typically pay out the top 15-20% of all finishers with the bulk of the prize pool going to those that finish within the top two percent. In order to double your money in GPPs you typically need to finish in the top 10%. Thus, our baseline expectations for a result that makes us feel good should be somewhere around 5-10% of the time we enter. The best players in the world might be able to double that rate of good outcomes, which means all of us are going to be disappointed more often than not if we evaluate solely on the results. Playing GPPs with the wrong expectations will lead to maddening results.

Instead of evaluating each week based on the profit/loss, DFS players should be evaluating their process. Did your lineup achieve the correlation and relative upside of strong GPP lineups? If you mass multi-entered were you able to generate more than 1% of your lineups in the top one percent of the GPPs you were playing? Were all your lineups created in a method consistent with your approach to correlation? Did your player pool feature players with attractive relative upside?

The best GPP players in the world will lose frequently. The idea is to refine a process which gives us a chance to bink a few top 0.1% lineups a year. Be prepared to endure stretches where the results don’t match up with the process and keep your focus on the quality of lineups you’re making.